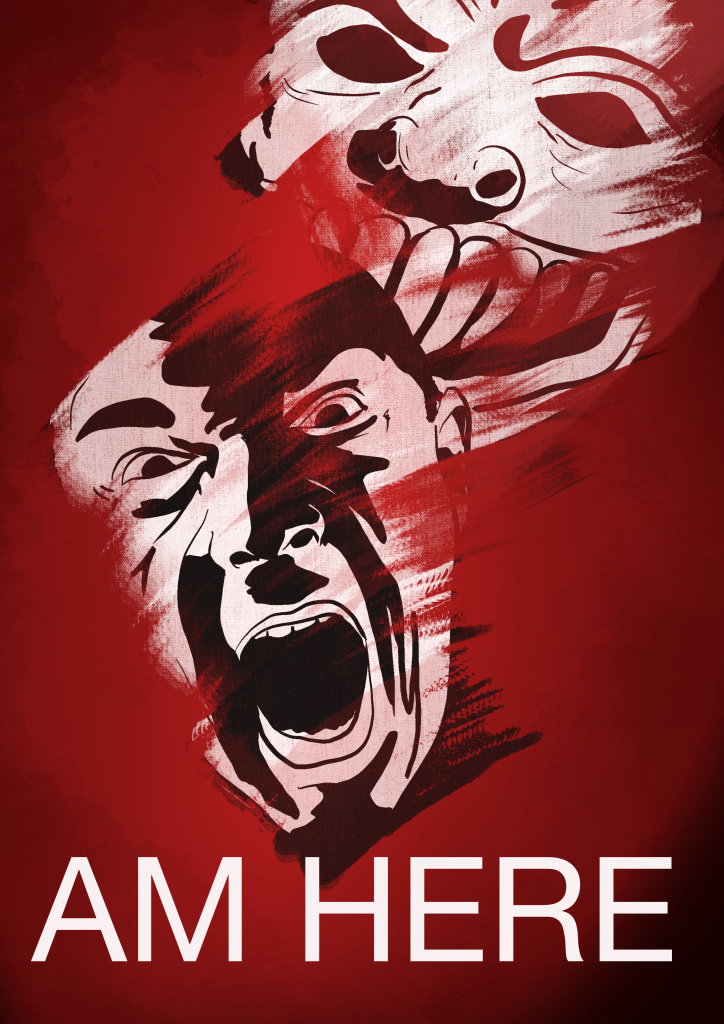

Am Here is a short film I made in 2022, but this is not a guide on how to make a short film. There is already plenty of information available on the practicalities of filmmaking. Instead, I want to understand how I briefly moved from being a passive member of a film festival audience, to creating a short film of my own and, maybe more precisely, why.

In the Beginning

I enjoy horror film festivals. I enjoy sitting in the dark and watching film after film, grabbing a coffee or a bite to eat and then watching a few more. But I do not network or engage with others, I hover on the periphery and that is where I stay. However, I have always wanted to make films and watching the shorts that play at Horror-On-Sea and Romford Horror Film Festival, made me feel that I could do something similar. I did not believe I could do it, but I knew it was possible.

Knowing vs Believing

The gap between knowing something and believing it, is huge. I had seen enough short films to know they could be made and with a small crew and not much money. So if others had done it, then logic dictated it was in my power to do it as well. The same goes for most things, playing the piano, writing a novel, driving a car. If someone has already done it, you can make a fairly solid bet that you can do it too. Although how well you do it is a different matter altogether. You could learn to drive a car and then on your first day out, crash it into a wall. The outcome was bad, but you still drove the car. In the same way, the film I might make could be an appalling mess, but somehow I was going to have to push that to one side. My aim was not to make the perfect film; my aim was to simply make something. More importantly, I was hoping to shift my thinking from one of knowing I could make a short film to actually believing it. But how? And what was stopping me from moving from knowing to believing in the first place?

Resistance

In his book The War of Art, Steven Pressfield, introduces the idea of Resistance and drags it into the light. We all instinctively know what Resistance is. If you are doom scrolling through social media, instead of writing your script, that is Resistance. It is that invisible force which holds you back, ties you down, throws a cloak of fear over you and hands out the excuses. It is the voice in your head which tells you, you are not good enough; you are stupid for even trying; you cannot do it, so do not bother. And then it distracts you with Candy Crush or TikTok. It is the thing which separates knowing from believing. And if you are reading this and throwing up your hands in frustration and howling ‘just do it!’ – have you just done it? Have you applied for that job? Renovated the bathroom? Composed that opera? Or are those things going to be done tomorrow? Because, tomorrow is one of Resistance’s greatest inventions.

Pat Higgins

Overcoming Resistance, moving from knowing to believing, can seem like an impossible task. However, if something or someone can give you the right push at the right time, then you can achieve a tipping point of self-belief, which will allow you to bridge that gap. In my case, the pushing force was the filmmaker Pat Higgins.

Pat Higgin’s masterclasses are one of the re-occurring events at Southend’s annual Horror-On-Sea film festival. The first talk I attended, Write a Bloody Movie in 30 Days gave me the kick I needed to complete the film script The Bedford Experiment. So in 2022, when Pat was due to give a talk about his, as of then, unreleased film Powertool Cheerleaders vs The Boyband of the Screeching Dead, it seemed like a good idea to go along.

Apart from discussing his own film, Pat delved into the practical idea of how to make a film. In particular, he referenced Robert Rodriguez, who posited the idea that you should write a film around what you actually have and not what you want. This is to stop your entire production process grinding to a halt, when you realise you don’t have access to forty camels and a space station.

But, as with all of Pat’s talks, although packed with great ideas and practical advice, the real force behind them was Pat’s infectious enthusiasm and ‘can do’ attitude. It was that, which made me believe, making a film was actually possible.

Keep It Simple, Stupid

Armed with this belief, a chink of light began to break through the Resistance force field. However, the negative voice was, and still is, ever present. But I realised I could dial it down, very slightly, by using one fundamental trick – having a plan, but keeping it simple.

A plan, even a stupid one, is better than no plan at all, as you can change a stupid plan. Without a plan, you may have a destination in mind, but with no road map to get there, you will flounder from the start – or at least I would. So I decided that my plan would take the form of a few basic rules. The rules were not original, but I decided to write them up and try my best to stick to them:

- Actually ask yourself the question – are you going to make a film. If yes, commit to it.

- The film will be five minutes or less.

- You should not spend any money. You can only use what is actually available to you. If you have access to a restaurant, a bar, an office, etc. That is your location. Use it.

- The film will not be perfect, not even close. You just have to make something that exists.

- You will enter it into a film festival. You have no control over it being accepted. The important thing is to get it entered.

All of the rules had solid reasons behind them. But, there was a sixth rule which sat outside the core five. It said the film had to be made in the traditional manner. A script had to be written, shots planned, a monster built, cameras and lights set up. The intention had to be, to create a film through the film making process and not simply an, on the fly, TikTok video.

S.M.A.R.T

All the rules could be seen as SMART goals. The acronym stands for

- Specific

- Measurable

- Achievable

- Relevant

- Time Bound

As a defined structure, it is not a bad one to follow, if you are trying to come up with a plan to get something done.

However, out of all of the goals, I would stress the importance of Time Bound. Your project must have a deadline. Without an end point, you will have no urgency to complete what you have started. Instead, you will just drag your feet, the dreaded Resistance will set in, and that will be that. So in my case, the deadline was the need to send the film off to a film festival, in particular Horror-On-Sea and Romford Horror. Both festivals were local to me and had cut off points for submissions, so Am Here had to be completed by their submission dates.

There was a second reason for sending the film into the ‘outside world’ – it would objectively exist. The film would have to be viewed by people divorced from the family / friends bubble, to decide whether or not it was suitable for their festival.

Obviously, the film being accepted by a festival was beyond my control, but this too was important. It crystallised what I could not control, which was how my film would be received. All I could control was the creative process. But if it was accepted, then I would have leapt that gap from passive festival goer to active film-maker.

Collaboration

Generally speaking, film making is a collaborative process, so unless I was going into animation, I needed a partner in crime.

The first person I turned to was Liam Jordan. He worked where I worked, is incredibly creative and had produced the art work for my second book The Big Stench, so he seemed like the ideal collaborator. And when I asked if he wanted to help me make a short film, he immediately said yes.

Once there were two of us, the question became, do we need more? It would seem that the obvious answer is yes. More people would make the process of making the film easier. But we were going to be shooting predominantly at night, in the middle of London and attempting to fit multiple people into a schedule would not be easy. Plus, with no money to spend, we would be relying on good will and that would only stretch so far.

In the end, we only used one other person, Michael Sprindzuikate. He assisted us on an entire Saturday shoot (which really helped us out), and more importantly, he composed the score which brought the entire short film together.

Positivity vs Bloody Mindedness

The people you have around you can dictate how your project goes. If you have someone who works with you and not against you, who sees mole-hills not mountains, who keeps pushing you forward, all well and good. But if you have someone who is constantly critical, who is always voicing your own internal doubts, then you may be better off without them.

Either way, it soon becomes clear that some people are filled with unbridled positivity and others are not. I am not. Facebook platitudes make me wince. However, if you pursue any kind of goal, it does require a degree of positive thinking. You had to believe the endeavour was worthwhile, otherwise why did you start it in the first place? So you have to strive to maintain that optimistic outlook, which convinced you to start your project. But you also need to acknowledge that it will waiver. So how do you cope when positivity wains? I would suggest you have to resort to resolute stubbornness, and that needs to be supported with a virtual tool-kit.

If you have come up with a series of rules or a plan, they can keep you on the straight and narrow. When you read them they will help to reset your focus. Also, sweat the small stuff. Break your large, overwhelming project, down into its constituent parts and concentrate on taking small steps towards your end goal. Because the undeniable truth behind, writing a novel, making a film or hammering out a script, is that it is less about talent and skill and more about rolling out of bed, turning up every day, and simply doing it.

And no matter what and no matter how slowly, you have to keep moving forwards. If you grind to a halt, it is very difficult to get yourself going again. So do not stop.

Bridging Gaps

Despite all the challenges, the horror short Am Here was made. It exists and was accepted by the Romford Film Festival where it was shown on the 25th February 2023. This was an amazing experience which I will never forget. I had set out to move from being a passive member of the audience to being a filmmaker, and I had succeeded. But how?

The more I think about it, the more I realise it was all about bridging gaps. Some of the gaps were practical, they required knowledge and information to cross over them. Others were more complicated and were to do with mind set: the gap between knowing and believing; between action and inaction; between committing and not committing. Each of those gaps can be crossed, but the belief needed and the skills required can be different every time. For example, making the film is very different to sending the film off to a festival – you have to learn new things and overcome the differing doubts that Resistance will throw at you. Equally, raising money to finance a film, is a very different and complex issue, to that of shooting a short with no money at all. But all these problems, all these gaps, need to be bridged. And if you persevere, if you continue moving forwards, eventually you will produce something. It may not be the thing you thought it would be when you started. It may be flawed beyond belief, but it exists and if you accept it, it could be the stepping stone on to something else. However, what that something else is, you will never know unless you bridge that first gap between knowing and believing.

The Big Why

‘Why did you make this film?’ ‘Why did you write this book?’ ‘Why now?’

These are the most difficult questions I can ask. Even now I do not have a complete answer. Yet I cannot, in my mind at least, over-exaggerate their importance.

The answers you arrive at (if you arrive at any answers at all), may not dictate the success or failure of your project, but it can certainly affect how you think of that project’s success or failure. And it can also affect whether or not you continue to pursue your chosen path.

If your answer is ‘I am making this thing as a calling card to break into the industry’ (whatever that industry may be) or ‘to make a lot of money’, or ‘to achieve worldwide fame’. These are reasonable answers, if problematic. Because your decision to pursue a given creative path now hangs upon some external gatekeeper, rewarding your endeavours. What happens if that reward never comes, you never break in, you never make money, your never achieve fame, what then? Do you just stop? And what does it mean if you can’t stop? What is the answer to all the big ‘why’ questions then?

In my case, the answer has little if anything to do with success. At least not now. If it did I would have packed up long ago. For me, the answer is embedded within the very act of ‘doing’ itself. I enjoy writing, I enjoy developing stories, building a structure and populating it with characters. I enjoy standing on the edge of the creative cliff and daring myself to jump. And maybe that is the answer to why I made Am Here. It was a leap into the creative unknown and you take that leap because sometimes you just do. However, even this is not an honest answer. I think the true why is buried far deeper than that, so I guess, I will just have to keep on digging and maybe make another film.