Directed by Paul Leni

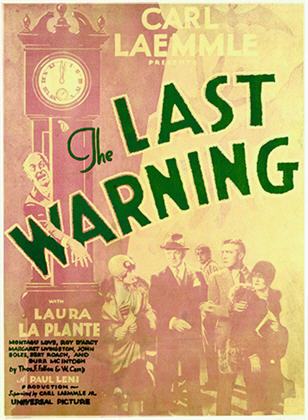

Paul Leni moved to America from Germany after an invitation from the president of Universal studios, Carl Laemmle (himself a German émigré). He had been working in the German film industry for several years and had finished making the eerie anthology film Waxworks in 1924, before travelling to the States in 1927. His first American film was The Cat and The Canary (1927), a seminal old dark house horror, which was both highly successful and the precursor to a whole host of imitations and remakes. He followed this with the now lost Charlie Chan mystery The Chinese Parrot (1927) before directing potentially his most well- known film, The Man Who Laughs (1928), with Conrad Veidt in the starring role. Finally, in 1929 The Last Warning received its full release, having been premiered on Christmas Day 1928.

The Last Warning is set in the Woodford Theatre on Broadway. The plot, as hackneyed as it was even for 1929, is centred around the murder of John Woodford (played by D’Arcy Corrigan), who dies onstage in front of a packed house. With the leading lady, Doris Terry (Laura La Plante), at the centre of several of the male leads’ romantic advances, including Woodford’s, she immediately becomes a prime suspect, along with the play’s director Richard Quayle (John Boles). However, before the coroner can inspect Woodford’s body, it disappears, never to be rediscovered and without a corpse no-one can be found guilty of a crime. Instead, the theatre falls dark and all the leading players go their separate ways.

Five years later, Arthur McHugh (Montagu Love), decides to re-stage Woodford’s final play with the original cast, all of whom return for fear of appearing guilty if they fail to attend. Yet they are greeted with a series of threatening notes, all written in the dead actor’s handwriting, telling them to leave the theatre, but McHugh persists. He is determined to find the murderer of his friend John Woodford, and believes the only way that will happen, is if he re-opens the show.

With a mysterious killer, secret passageways, clawing hands, dozens of suspects and the entire story confined to an abandoned theatre, The Last Warning is an unsubtle horror-thriller clearly in the mould of The Cat and the Canary. However, this lack of subtlety succeeds in giving the film a direct, no nonsense focus, although it can and does lead to accusations of the film being both derivative, simplistic and lacking in depth. Such criticisms are, from a narrative perspective, fair. But what they fail to take into account is a film brimming with cinematic flourishes as well as possessing flashes of Leni’s expressionistic past.

Invariably, when anyone thinks of German Expressionism they immediately recall Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919). It was this film which epitomised the ideas of German Expressionism as a movement dedicated to reflecting the on-screen character’s inner struggles and torments by showing a distorted version of reality. Within The Last Warning, this subjective, emotive representation is visible primarily in the depiction of the Woodford Theatre. It is a character in its own right and Leni makes superb use of sets originally built for The Phantom of the Opera (1925). The theatre is deliberately designed to look like a brooding face filled with threat and menace which comes alive after five years, when the cast and crew return, its eyes opening as if after a long sleep.

Throughout all three of his surviving American films, Leni looked to be adapting his story telling techniques to match the needs of the American film industry, which wanted to tell dramatic stories yet do so in a stylistically standardised way. Certainly, there appears to be an evolution in style from The Cat and the Canary to The Last Warning. But, as Leni found to his favour, the horror and thriller genres were always amenable to Expressionistic émigrés including Fritz Lang and Karl Freund. It allowed such filmmakers to inject their movies with a particular subjective style, which arguably still exists within those genres today, and meant they did not have to entirely abandon their expressionistic roots.

With subjective stylisation in mind, The Last Warning’s most jarring aspect is the opening montage; a jazz infused, kaleidoscope of shots all seeking to represent the vibrant and exotic Broadway milieu. Stylistically it certainly sits apart from the rest of the picture, yet it kicks the film into life, especially because it neatly segues into the police arriving at the theatre to investigate Woodford’s death, rather than existing as a standalone sequence, separate from the main narrative. This kinetic drive is present throughout the film; from the moment when Quayle, the play’s director, dramatically calls for the curtain to be lowered and the camera dives beneath it, to stare at a panic stricken audience, up to the film’s climax where the killer is swinging upon a rope and the camera assumes his dizzying point of view.

However, in my opinion, the most accomplished sequence is where a detective leaves Doris Terry’s dressing room, twirling a small flower between his fingers, believing it to be an incriminating piece of evidence. His slow walk towards us, until the flower looms large in the frame, is so assured it seemingly pre-echoes Hitchcock’s shot in Suspicion (1940), where a potentially poisoned glass of milk is carried up a flight of stairs into a threatening close-up. And ultimately that is what The Last Warning is, it is an accomplished piece of work by a consummate professional at the top of his game.

Although by default, many directors in the 1920’s were pioneers of an evolving language, Leni was at the forefront of that crowd. This makes his untimely death at 44 of sepsis (caused by an infected tooth), all the more tragic. It is therefore a shame that The Last Warning is somewhat undervalued when reflecting on Leni’s remaining American films. It deserves to sit alongside both The Cat and The Canary and The Man Who Laughs as an important work by a director largely forgotten by mainstream, cinema history.

Note:- the gif used at the start of this review was created from the trailer for the 4K restoration print by Flicker Alley.